About This Title

Marosa di Giorgio was born in Salto, Uruguay, in 1932. Descended from Italian immigrants of Tuscan origin, she and her sister Nidia were raised Catholics in the countryside. Her first book, Poemas, was published in 1953. Also a theatre actress in the 1950s-1960s, she participated in almost thirty productions. In 1978, after the death of her father, she moved to Montevideo, where she lived until she died of cancer in 2004. Like Walt Whitman, di Giorgio expanded the same work throughout her career: Los Papeles Salvajes, her collected poetry, which unites fourteen books. Since her poems inhabit the same imaginative world, they can be read as one long meditation, which di Giorgio described as a forest in which she planted more trees.

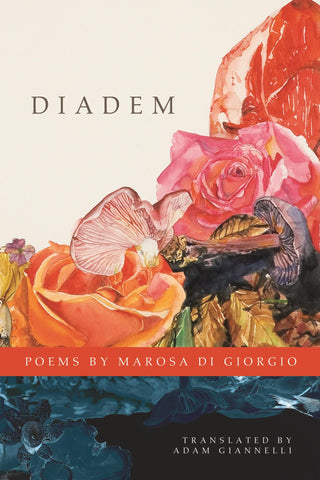

Excerpt from Diadem: Selected Poems

“Green, pink, ringed, hand drawn. It’s said they have relations with themselves and are visible when they shudder.

Or rigid like a finger they manage to drink in the fountain of roses. They’re related to roses, bromeliads, and the pear tree. Some consider them only reveries that represent the sins of men.

But I, since I was a girl, in the light of the sun and moon, believe in them; I know they’re real.

I saw them open their lips, black as the night, their gold teeth, after an almond, a pumpkin seed.

To face one’s own mark, playing and fighting; and in love without others, to twist until death.”

Praise for Diadem: Selected Poems

“Since the publication of her first books in the mid-1950s, Marosa di Giorgio has introduced a seemingly indefinable element into Uruguayan literature. Angel Rama and Roberto Echavarren regard her as one of the most original and brilliant descendants of the Uruguayan-born Lautreamont. Other commentators portray her as an eccentric whose poetic prose is virtually synonymous with the idiosyncratic … She is therefore a writer who has been praised but also marginalized – insofar as she is repeatedly held up as the ‘mad woman’ of contemporary Uruguayan letters – because of a critical tendency to theorize negatively the very aspect of di Giorgio’s surrealist practices for which she has become most famous: her visionary escapism.”—Kathryn A. Kopple, the Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies

Publication Date: October 16, 2012

ISBN: 978-934414-97-2

© BOA Editions, Ltd. 2012